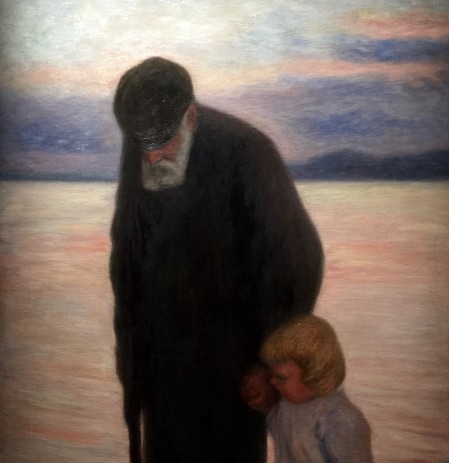

Serge Attukwei Clottey and GoLokal, My Mother’s Wardrobe, performance at Gallery 1957, 6 March 2016, courtesy the artist and Gallery 1957, photo by Nii Odzenma

On March 6 2016 as Ghana marked 59 years of independence, Gallery 1957, a new gallery with a curatorial focus on contemporary Ghanaian art by the country’s most significant artists celebrated its inaugural exhibition. With over 400 people in attendance, My Mother’s Wardrobe, a new creative work by Serge Attukwei Clottey captured a diverse and equally enchanted audience.

Founded by Marwan Zakhem, the gallery has evolved from over 15 years of private collecting and offers an ideal location for both local audiences and international visitors to discover new artists, and to gain a deeper understanding of the breadth of their practice through curated exhibitions. With an initial curatorial focus on contemporary Ghanaian art, the gallery will present a programme of exhibitions, installations and performances by the region’s most significant artists under the creative direction of Nana Oforiatta Ayim. The artist, Serge Attukwei Clottey, is the founder of Ghana’s GoLokal performance collective and the creator of Afrogallonism, an artistic concept commenting on consumption within modern Africa through the utilisation of yellow gallon containers.

Based in Accra and working internationally, Clottey’s powerful testimony to his mother in the aftermath of her death explores narratives of personal, family and collective histories. In continuation of the artist’s established use of assemblage, he considers the value of material as a tangible experience of loss. His works examine the powerful agency of everyday objects, with particular focus on the significance of personal clothing.

Serge Attukwei Clottey and GoLokal, My Mother’s Wardrobe, performance at Gallery 1957, 6 March 2016, courtesy the artist and Gallery 1957 Photo Credit: Nii Odzenma

I recently interviewed Nana Oforiatta Ayim, founder of ANO, and Creative Director of Gallery 1957 to gain a better understanding of Clottey’s work, Gallery 1957, the creatives industry and intrinsically the role of art in exploring and reconciling Ghana’s past and present.

Tell us about yourself

I write, make films, and work as a cultural historian, which involves uncovering or creating new narratives, particularly of what is now known of Ghana, and the regions that surround it. I live in Accra, Ghana, where I founded and run the cultural organisation ANO, and where I am the Creative Director of a new art space, Gallery 1957.

Tell us about ANO, (what does it stand for) how did it come about and what inspired its inception?

The name ANO is an aberration of the Akan word εno, which means grandmother. In Akan mythology, an old woman or grandmother is the ancestress of humankind. And even though, at traditional occasions, at festivals and funerals, it is often the men that play the role of elders, it is the old woman they go out to spiritually consult. I liked this notion of the origin of beings being female, of this alternative history to the dominant one in our largely Christian country, which is of the first human being a man. ANO is largely about the uncovering and re-writing and -formulating of alternative, more covert histories to challenge dominant, sometimes reductive ones. –

It is also a suffix in the language Esperanto, which I love for its ideal of a common language, one that would transcend national divisions, and that means belonging. In a global narrative, which has for so long been dominated by one side, and in which our cultural offerings, our philosophies and ways of being, were to some extent denigrated, I very much liked this ethos of belonging, of us all sitting at the same table, as equals, with all right to be there, no one sitting higher or lower than the other, most especially in a world that still differentiates on a spectrum from first to so-called third world countries.

The third meaning for it is as a short form of A.N. Other, a pseudonym for the unknown or anonymous. I remember going to museums in Europe when I was younger, and often seeing very sparse plaques alongside sculptures or masks, giving very little context or meaning to why they were there, where they were taken from, who created them, and from within what greater narrative they came. There was a sense that these objects like so much else that came from the continent of Africa were raw material, objects of inspiration for ‘greater’ artists with greater understanding, consciousness and agency. And so ANO is also about retelling histories on their own terms or at least attempting to, and in this way giving them more rounded truths.

Has ANO changed since its inception? If so, which significant changes have happened?

I first started working with the notion of ANO as a mobile platform in 2002 curating exhibitions at the Liverpool Biennial, organising events at the Royal Festival Hall in London, making films etc. The most significant change has been ANO’s settling into a physical space in Accra, and also expanding into more large-scale encompassing projects, like the Cultural Encyclopaedia.

Serge Attukwei Clottey, Love and Connections, 2016, Plastics, wire and oil Paint, 95 x 89 inches, ©the artist, courtesy Gallery 1957, Accra

How do you choose the artists who receive residency such as in the case of Serge Clottey?

It all happens quite organically. ANO is not a static institution with fixed paradigms and goals. It has been very porous and open, listening to and seeing what works, what synergies there are with other creatives, and then acting upon them. The residency programme emerged from shared interests and the notion that mutual collaboration could be of benefit.

What gap if any do you see in the art and creative works industry in Ghana?

I feel that whatever gaps there are are being addressed by people’s ingenuity. New institutions are springing up, like Gallery 1957 and the Archiafrika Gallery of Design and Architecture. The government is putting some funding into the arts, even if it could do a lot better. Institutions, like the National Theatre are starting to engage with young artists, like Ibrahim Mahama and Serge Attukwei Clottey, and of course artists keep pushing at their own boundaries. I think it is a very good time creatively in Ghana, and I’m excited to see what emerges over the next few years.

What role do you see art playing in creating a platform for reconciling socio-cultural, economic and political discourse beyond ANO?

I think art provides another way of seeing, of thinking, of understanding. I think it highlights things that might be obvious to everyone around, but that are not being addressed, as well as things that might not be obvious at all. I think that the more attention is paid to it, the deeper our engagement with our environment will be, as well as that with our own selves, and that in itself is the strongest foundation for any discourse or development.

You have been quoted as saying the following profound words on reconciling art and loss with regards to Clottey’s work:

“According to custom in many parts of Ghana, a person’s wardrobe is locked up for a year after their death then released to relatives, often leaving the person’s offspring with little or nothing of the material memory of that person. Textiles and materials in Ghana, and other parts of West Africa — each weft, line or mark — are potent carriers of memory, of communication, and the artist weaves into his sculptures subtle traces of loss, remembering, and of rebirth.”

In your view, does Clottey’s artistic work resonate with most Ghanaians?

I am going to do a series of talks at Gallery 1957 around his works for schools and universities and workers, and I’m very excited about the exchanges that will happen as a result of that. I think Serge’s work is deeply embedded in Ga cosmogony and offers an aesthetic and provocative way of looking at our past and recreating our future, and it is always a spectacle, which in itself excites people’s attention. The challenge now is to get the work and the discourses around it seen by more people than those naturally drawn to art, and I hope to do that with a series of films around Serge and other artists, their work and the deeper themes.

Serge Attukwei Clottey and GoLokal, My Mother’s Wardrobe, performance at Gallery 1957, 6 March 2016, courtesy the artist and Gallery 1957, photo by Nii Odzenma

My Mother’s Wardrobe is a result of Clottey’s residency with ANO, whose remit is to uncover hidden and alternative, personal and collective histories, which make up what is now known as Ghana. Can you tell us about other projects you are working on and what to expect in 2016?

There will be a lot of projects in 2016! Another collaboration with Serge on the Korle Lagoon around the themes of nature and its invasion and the mythologies around this within Ga philosophy, as well as a book and film on his work. A collaboration with Zohra Opoku for Gallery 1957, as well as a book and film on her produced by ANO. And an exhibition with Serge, Zohra, and Ibrahim Mahama at the end of the year at LACMA in Los Angeles, for ANO’s Cultural Encyclopaedia project. There will also be a preliminary tour of the country with what I call Living History Hubs, mobile museums, to gather and exhibit material cultural and upload it onto the Cultural Encyclopaedia site. And finally, an exhibition at Gallery 1957 with young artist and performer, Elisabeth Efua Sutherland which resonates deeply with ANO’s remit, as its subject is the role of the feminine in myth-making.

What advice would you give to upcoming artists in Ghana?

To listen deeply to whatever it is that resonates with them the most and to follow that impulse. To look around and see what inspires and challenges them in their environment, as well as outside of it. And to keep working at it, despite all the obstacles, and even without initial support; to create and express even if it is on their street corners or in their family compounds or in a market place, and to keep delving. I feel like it is consistency and integrity of purpose, as well as clarity of expression that draws support, in whatever form, to itself.

Lastly, why is this exhibition a must see for all?

The exhibition is a must see, because Serge is a very talented artist at the full potency of his creative expression. He is experimenting with form and he is delving into the various layers of his environment and bringing them forth in ways that are unexpected and that enchant and expand. The exhibition is a testament to ingenuity, to diligence, to just what is possible, and because of that I think acts a source of inspiration.

This article first appeared in my blog post @ Africa at LSE .

Among these options include: joint interpretation of treaty provisions; amending treaty provisions; replacing outdated treaties; consolidating treaties; managing relationships between co-existing treaties; referencing global standards; engaging multilaterally; abandoning unratified old treaties; terminating existing old treaties; withdrawing from multilateral treaties. Important to note is that each option has pros and cons, therefore determining the best option requires ‘a careful and facts- based cost-benefit analysis, while addressing many of broader challenges’. It is submitted that the best option is one which is balanced, predictable and suitable for sustainable development.

Among these options include: joint interpretation of treaty provisions; amending treaty provisions; replacing outdated treaties; consolidating treaties; managing relationships between co-existing treaties; referencing global standards; engaging multilaterally; abandoning unratified old treaties; terminating existing old treaties; withdrawing from multilateral treaties. Important to note is that each option has pros and cons, therefore determining the best option requires ‘a careful and facts- based cost-benefit analysis, while addressing many of broader challenges’. It is submitted that the best option is one which is balanced, predictable and suitable for sustainable development.

Credit: Africa at LSE

Credit: Africa at LSE

Credit: Goodreads

Credit: Goodreads

Recent Comments